The focus of this blog is the tradition of palaeography, i.e. the study of historical handwriting. This skill is important for transcription of ancient, medieval and post-medieval texts and for understanding the development of writing itself. This blog attempts to introduce the topic by covering some of the key ideas that are relevant to palaeographers as they attempt to decipher a post-medieval text.

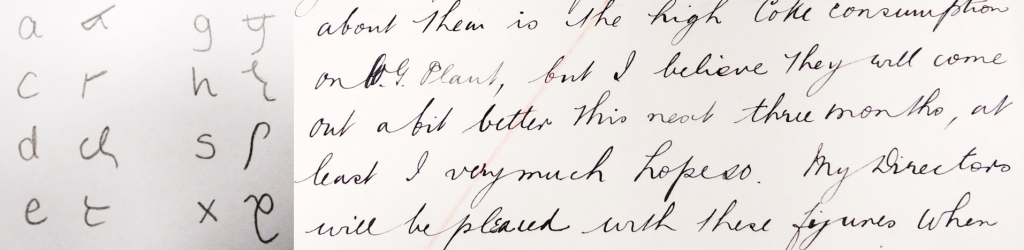

Throughout the centuries different styles of handwriting have become popularised. The modern handwriting style was founded with the italic style in the 14th to 16th centuries. This image shows some of the ways in which letters have been written in different styles of handwriting. This expresses why palaeography is a learned skill, since without knowledge of these letter shapes their presentation might be quite confusing to someone trying to read a document.

From looking at handwriting we can often see stylistic flairs that it helps to learn when interpreting an individual writer’s text. This example from our gas company collection (20th century) demonstrates that the scribe often joins words together and exhibits the different ways they write the letter ‘t’. Whilst it is useful to familiarise yourself with a writer’s style, it is also important to recognise that it may change throughout their life. Therefore, alongside learning the popular styles of the time, it is helpful to also pay close attention to specific individuals and the way they write.

Spelling could also differ, e.g. said being spelt sayd, and scribes often used abbreviations to shorten words, e.g. ‘wch’ for ‘which’ uses superscript letters. It is these historic ways of writing that have fallen out of fashion. If we consider modern language we notice that it changes all the time, whether that is the invention of a new slang term, a word to describe a scientific idea or abbreviations popularised via social media.

Transcribing a text can often feel like solving a puzzle. Making decisions about what handwriting style, date and individual letters are present discloses the content and, occasionally, context of historical documents, allowing you to glimpse aspects of life from centuries ago. We run palaeography courses here at Heritage Quay for students and researchers, so if you are interested please send us an email at archives@hud.ac.uk. If you want to read more about the topic and practice some examples, check out The National Archives pages at http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/palaeography/default.htm.

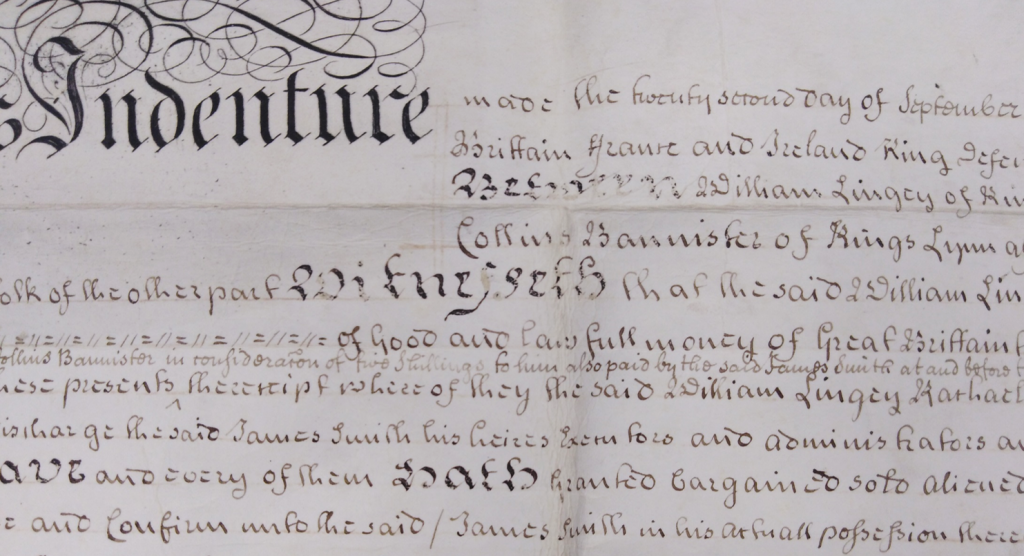

If you fancy having an attempt at transcribing, make sense of the image below from a 17th century Indenture which is one of the earliest legal documents we have at our archive. This is just a snippet of the document so the sentences aren’t complete. The answer will be in the comments below so don’t scroll till you’ve had a go.

If you’re a University of Huddersfield student the archive runs regular classes on how to pick up skills in palaeography 1500-2000! Just contact the archive for more information – archives@hud.ac.uk

Answer-

Indenture made the twenty second day of September

Brittain France and Ireland King

Between William Lingey of

Collins Bannister of Kings Lynn

of the other part Witnesseth that the said William

of Good and Lawfull money of Great Brittain

Collins Bannister in consideration of two shillings to him also paid by the said James Smith at and before

presents the receipt where of they the said William Lingley Rachael

the said James Smith his heires executors and administrators

and every of them hath granted bargained sold aliened

and confirm unto the said/ James Smith in his actual possession there