Now things are returning to ‘normal’ and we’re all starting to venture out into the wider world again, we thought now would be a good time to look back on what Heritage Quay staff have been doing whilst working from home during lockdown, what we’re up to now we’re back on site, and our plans for the future.

Working from home

You’ll all have your own opinions on the pros and cons of home working. Personally I liked the flexibility that it gives you, since it’s simply a matter of logging on to your PC with no trains or buses to catch. But there is the downside of not being able to chat to colleagues in the staffroom nor being able to have impromptu meetings (video calls are not always an ideal substitute for face-to-face interaction, after all). Not to mention, if your house is anything like mine, that the constant knock at the door announcing the arrival of a parcel meant a lot of leaping out of your desk chair and snatching up your keys. And of course, our research room was closed to the public, meaning they couldn’t get hands on with our archival material. It’s always interesting to chat to researchers about their projects, and I missed that.

One advantage of working from home was that it gave us a chance to do a bit of digital housekeeping. Our online catalogue has had a bit of a tidy, and we’ve also looked at streamlining our digitisation process, which will be a big help going forward.

We’ve been showing our social media channels more love and sharing some highlights from our collections through them. This has been a lot of fun, and gave us a chance to be a bit creative. Taking part in the History Begins at Home (#HBAH) campaign and ARA Scotland’s awesome #Archive30 has been especially enjoyable (hoping they’ll run #ArchiveAdvent again this year).

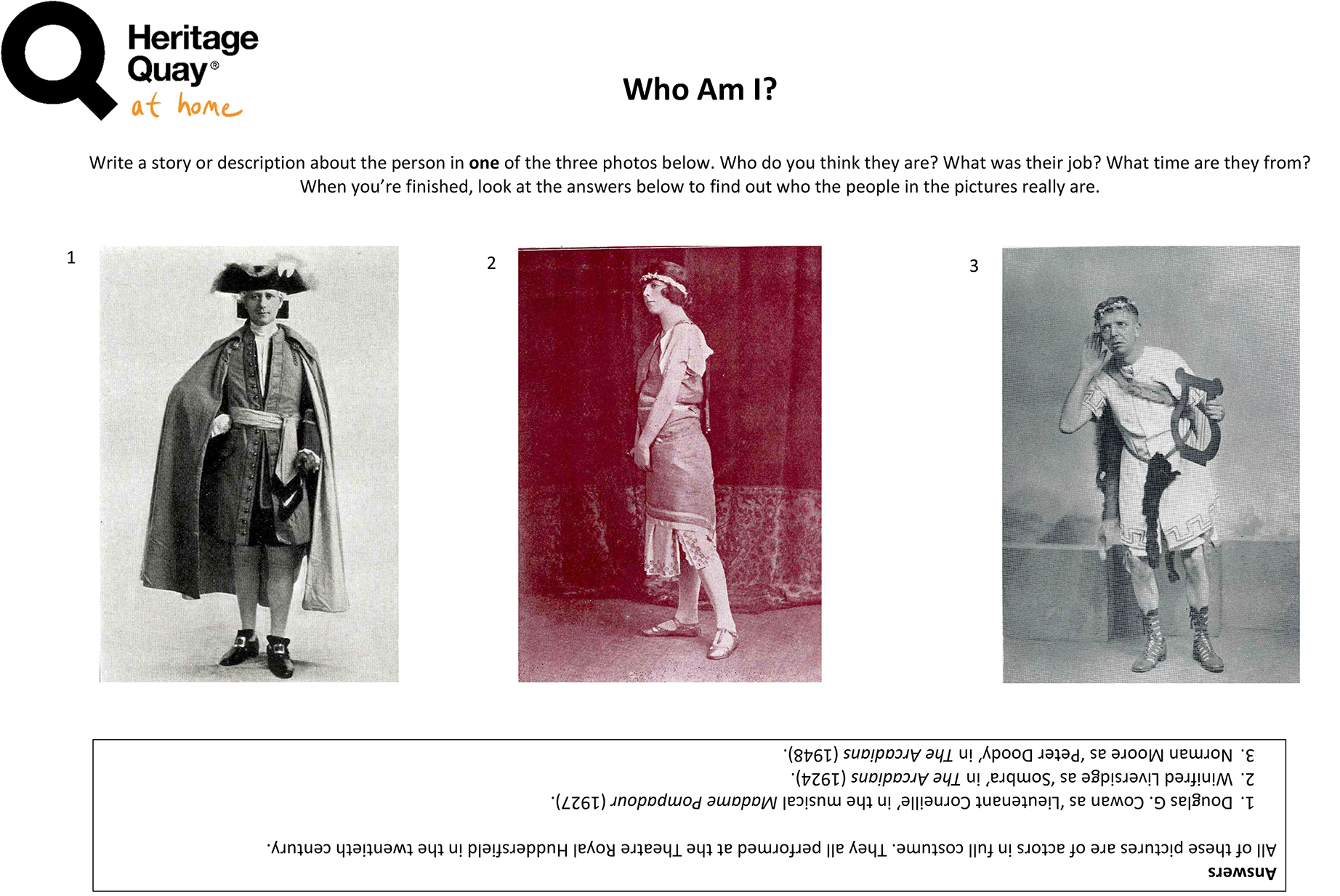

You might have seen earlier posts about our educational package as part of our Heritage Quay at Home project. As one of the members of the HQ team who developed the worksheets for home schooling, I must say that putting the package together was a lot of fun. We hosted an online Sports Study Day with two sessions on England Netball and Rugby Football League, which we received great feedback on from those who attended – there were certainly some engaging discussions going on between participants. My favourite project of ours from the first lockdown period has to be the scavenger hunt. Coming up with clues was sometimes tricky, but I certainly flexed my writing muscles!

What we’re up to now

One of our top priorities now that we have access to our physical collections once more is working through our (rather long) back catalogue of enquiries from our researchers, who have been very patient and understanding in the meantime. There’s also lots of cataloguing work to catch up on – not including the 100+ boxes of some very exciting stuff that we recently acquired (watch this space). We’ve also been trialling some in-person appointments in the hope of re-opening fully to the public in the autumn.

I don’t mind admitting that coming back to campus was a little daunting initially, and it took some time to get used to the health and safety measures, but after a while you built habits. I have a regular routine for wiping my desk at regular times. Working with the archives in the strong rooms requires a little bit of coordination between staff to maintain social distancing, but it’s manageable. If you’re working with lots of boxes, you ‘adopt’ a trolley for the day and put your name on a piece of paper so everyone knows not to touch it, making sure to wipe it down before home time.

What’s next?

While we hope to re-open the HQ space and research room to everyone soon, in the near future we’ll be introducing remote sessions for the benefit of researchers who are unable to visit us in person. This will allow the researcher to view archive material via video link, with one of our Archive Assistants on hand to help. We’ve invested in some snazzy camera equipment, which researches can view material through, and are currently having fun testing it.

The last year and a half has been challenging for us, as it has for everyone, but it’s also been a chance to develop and try new things. We’ve got lots of exciting projects planned for the future and we’re looking forward to welcoming our lovely researchers back to our research room!

You can check our website for updates on reopening: https://heritagequay.org/visit/